by Chris McGowan

(published on March 16, 2016 in The Huffington Post)

(published on March 16, 2016 in The Huffington Post)

Vasconcelos was a master of the berimbau, a musical bow from Bahia with a single metal string and a resonating gourd, which he turned into a unique solo voice. His peer Airto Moreira called him “the best berimbau player in the world.”

He was also adept with most other Brazilian percussion instruments, which he combined with layered vocals, handclaps and body percussion. He created irresistible rhythmic waves or engaged in spirited dialogues with other musicians. Sometimes he created dense atmospheres of sound, in which rustles, rattles and rumbles moved with captivating rhythms or clashed in unearthly cacophony.

“He went beyond keeping time and creating just a mood, his thing was deep—he created a sense of place and time in music. When you heard him play, you understood something more about the music. He dove into the story of each song and gave you a reason to stay on. Very few percussionists can do that,” comments Grammy award-winning jazz vocalist Luciana Souza.

Vasconcelos’s collaborations with leading figures from free jazz and fusion put him at the forefront of the world’s percussionists. Naná generated such a distinctive voice with his percussion that he was able to hold his own in duos and trios with musical heavyweights. He teamed with Egberto Gismonti on Dança da Cabeças and Duas Vozes, with Don Cherry and Collin Walcott for three Codona albums, with Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays on As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls, with Jan Garbarek and John Abercrombie on Eventyr, and with Milton Nascimento and Herbie Hancock on Miltons.

Juvenal de Holanda Vasconcelos (Naná was his nickname) was born on August 2, 1944 in the coastal city of Recife, which is home to a rich musical heritage that includes genres like maracatu and frevo. As a youth, he learned to play the drums of maracatu as well as most other Brazilian percussion instruments, and became adept with the berimbau, an instrument associated with the martial art capoeira.

In the late ‘60s, he toured with Gilberto Gil and was part of Quarteto Livre with northeastern singer-songwriter Geraldo Azevedo. For a time he was part of the seminal Som Imaginário band, which mixed Brazilian music, jazz and rock and backed Milton Nascimento. His playing caught the attention of saxophonist Gato Barbieri, with whom he started touring. He subsequently spent a few years in Paris and while there worked with disturbed children in a psychiatric hospital, using music as a form of creative therapy. His experiences there would inform his work: Vasconcelos saw how music could transform and improve people’s lives. During this era, he found time to record his first solo album, Africadeus (1973).

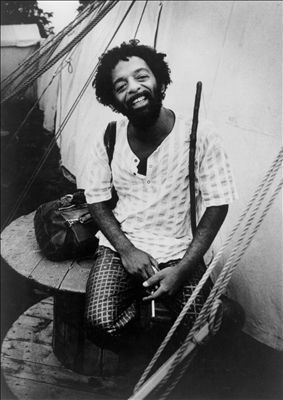

Naná Vasconcelos and Milton Nascimento

Collin Walcott, Don Cherry, Naná

In 1979 he formed Codona with trumpeter Don Cherry and percussionist Collin Walcott. The trio released three highly regarded albums for ECM that mixed free jazz and cross-cultural improvisation.

Don Cherry, Collin Walcott, Naná

Vasconcelos expanded his audience greatly when he played percussion and sang with the Pat Metheny Group, beginning with Metheny and Mays’ 1981 As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls. “He was a total joy to work with,” keyboardist Mays told me in an interview for my book The Brazilian Sound. “One of the things that I most enjoyed about playing with Naná was that he was interested in working with me as a synthesizer player to come up with combination textures that neither of us could do alone. He took things a step further, using his voice together with his instrument and with my instruments. Naná broadened our soundscape, and he added charisma, another focal point of attention on stage.”

On his website, Pat Metheny adds, “In addition to being one of the best percussionists in music, Naná was an amazing, wonderful person. Everywhere he went (berimbau always nestled on his shoulder) he made friends and brought an infectious joy to the people around him. His laugh was contagious and his ability to bring happiness to any situation spilled over to the bandstand.”

Naná (top left) with Pat Metheny (center)

Vasconcelos also appeared on Metheny’s Offramp and Travels, before moving on to other projects. Along with releasing his own albums, Vasconcelos enhanced the works of many artists, in and out of Brazil. One noteworthy example is Lenine’s Na Pressão (1999), on which Naná played shakers, a talking drum and other instruments on the album’s dramatic title track. He also recorded with Brazilian musicians Marisa Monte, Caetano Veloso, Alceu Valença, Eliane Elias, Joyce, Toninho Horta, Luiz Bonfá, Badi Assad and Mônica Salmaso, along with those mentioned above and many others.

Egberto Gismonti and Naná Vasconcelos

In addition, Vasconcelos recorded and/or performed with Miles Davis, Art Blakey, Tony Williams, Ralph Towner, Paul Simon, B. B. King, the Talking Heads, Leon Thomas, Jean-Luc Ponty, Jon Hassell, Harry Belafonte, Claus Ogerman, Ginger Baker, Jack DeJohnette, Carly Simon, and the Yellowjackets.

Nana’s many fine solo works, such as Saudades for ECM (1979), Bush Dance (1986), Rain Dance (1989), Storytelling (1995) and Chegada (2005) are like sound encyclopedias, beautiful elaborations of rhythmic and textural possibilities. His album Sinfonia and Batuques won a Latin Grammy award in 2011 for Best Native Brazilian Roots Album.

Vasconcelos returned every year to Recife to take part in Carnaval celebrations and lead a large group of maracatu drummers and singers, one of his many projects that supported Afro-Brazilian culture. When he died, these and other local musicians paid musical tribute to him in a procession through the streets of Recife, on the way to where he was buried.

Brazilian keyboardist, composer and music educator Antonio Adolfo reflects, “He grew tremendously when he traveled and lived outside Brazil. He developed a tremendous technique mixed with all his cultural background—presenting the berimbau to the world along with all his work with percussion in general—and became one of the most important percussionists of all time.”

_______

No comments:

Post a Comment